In early 2019, an outbreak of measles centered around Portland, Oregon, and nearby Vancouver, Washington, infected around 70 people, most of them children. The Clark County Public Health Department declared the outbreak a public health emergency, stating that about 60 of those infected were never given the measles vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that kids get the measles vaccination early in childhood; for herd immunity to be effective, 93 to 95% of the population must have received the vaccine. In Clark County, however, only 78% of children ages six to 18 had received the recommended two doses of the vaccine by the end of 2018.

While the large majority of children across the U.S. do have the recommended vaccinations to protect them against infectious diseases, a small segment doesn’t. That small part of the population is growing, meaning children aren’t getting their shots. The rate of unvaccinated toddlers is growing year after year. For the CDC, that is a huge concern because vaccines have saved hundreds of thousands of lives in the U.S. and prevented millions of hospitalizations. Outbreaks have begun popping up all over the country. Almost 200 people were stricken with measles in New York State, and several cases were reported in different counties in Texas.

This trend may not be limited to the U.S., however. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared vaccine hesitancy—resisting vaccination due to safety fears, complacency about infectious diseases, or difficulty accessing vaccines—as one of 2019’s top 10 threats to global health.

In this modern age of instant information and disinformation, things can get confusing quickly. Bad information about vaccines for children can mislead parents, making it tough for them to know what’s true and what’s not. Parents only want to act in the best interests of their children and to make informed decisions. Sorting through the Internet to find facts instead of fiction is hard, so here are some common myths and facts about vaccinations for kids to help clear the air.

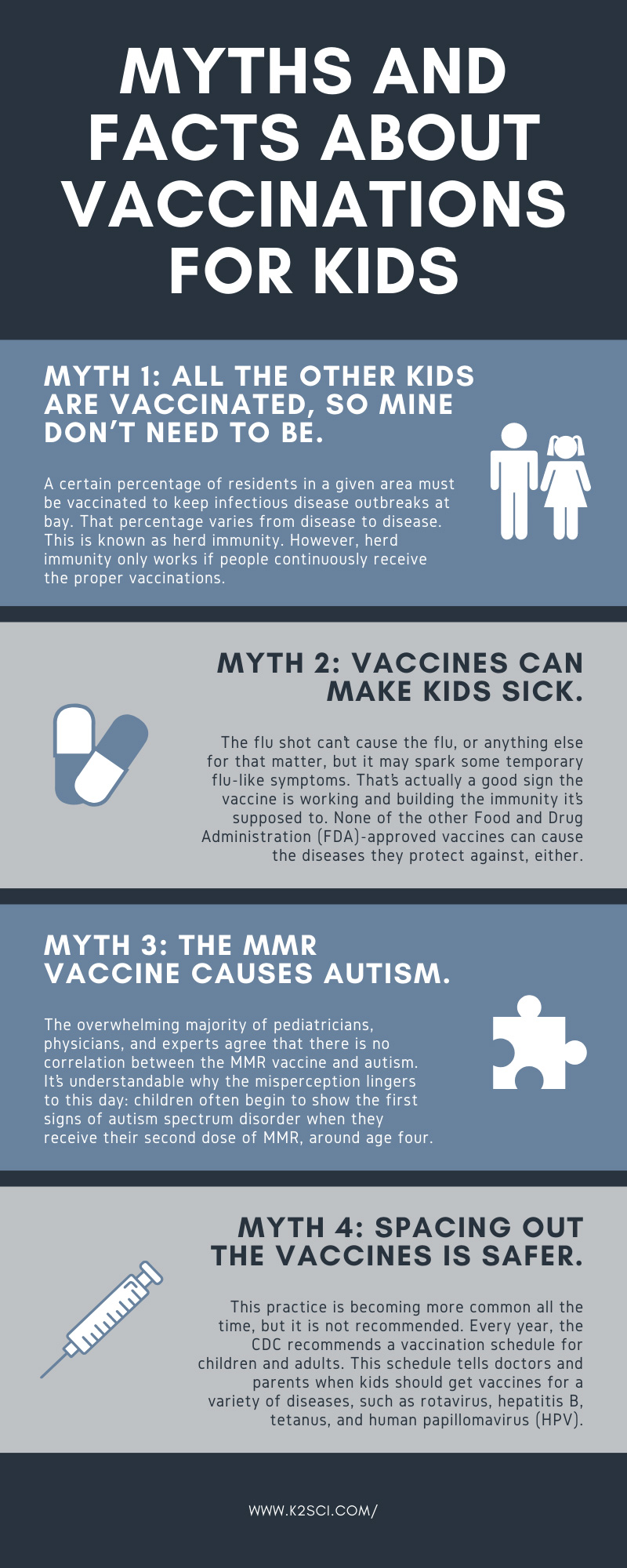

Myth 1: All the other kids are vaccinated, so mine don’t need to be.

A certain percentage of residents in a given area must be vaccinated to keep infectious disease outbreaks at bay. That percentage varies from disease to disease. This is known as herd immunity. However, herd immunity only works if people continuously receive the proper vaccinations. Some people, such as infants and those with illnesses that compromise their immune systems, are unable to receive shots, and if the immunity percentage drops too low in their community, they’re likely to get sick if an outbreak does occur. Therefore, you can’t always count on others’ immunity to protect you or assume that they have been immunized in the first place.

Myth 2: Vaccines can make kids sick.

Has your child ever gotten a shot and then come down with an illness? This is a common complaint associated with the flu shot. Many parents and people in general grouse that as soon as they got the flu shot, they got sick. There’s little doubt that the person got sick, but the reasons behind it are specious. It was probably just a coincidence that they got sick after getting the flu shot. Most influenza vaccines are given in the fall and early winter, which is when respiratory viruses and other illnesses tend to circulate. Plus, it can take up to two weeks for the flu vaccine to become effective, so the person may have contracted the illness prior to receiving the shot.

The flu shot can’t cause the flu, or anything else for that matter, but it may spark some temporary flu-like symptoms. That’s actually a good sign the vaccine is working and building the immunity it’s supposed to. None of the other Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccines can cause the diseases they protect against, either. But, like the flu shot, they can cause temporary side effects such as swelling at the injection site or a mild fever. If your child does experience any mild side effects, that’s no reason to avoid the next cycle of shots. A study conducted in 2017 found that the chance of a minor, recurring side effect was less than 50%, and the chance of a serious reaction was less than 1%.

Myth 3: The MMR vaccine causes autism.

Children usually get two doses of the MMR vaccine at 12 months and four years of age. A 1998 study published in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, purported to link the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine to autism in children. That study grabbed headlines all over the world and generated a lot of fear. In the 20-plus years since the release of that study, however, it has been soundly debunked and retracted. The overwhelming majority of pediatricians, physicians, and experts agree that there is no correlation between the MMR vaccine and autism. Andrew Wakefield, the lead author of the study, was actually forbidden from practicing medicine in the United Kingdom due in part to the fact that he falsified some of the study’s findings. It’s understandable why the misperception lingers to this day: children often begin to show the first signs of autism spectrum disorder when they receive their second dose of MMR, around age four. Since the debunking of that study, though, several other studies have found no connection between vaccines and autism.

Myth 4: Spacing out the vaccines is safer.

Before the age of six, children can get as many as 29 shots, not including flu shots. Some people worry that getting multiple vaccines at once will harm their children. The fear is that this influx of vaccines will overwhelm the child’s immune system. Some parents then request that doctors delay or spread out the shots. This practice is becoming more common all the time, but it is not recommended. Every year, the CDC recommends a vaccination schedule for children and adults. This schedule tells doctors and parents when kids should get vaccines for a variety of diseases, such as rotavirus, hepatitis B, tetanus, and human papillomavirus (HPV). The CDC publishes this schedule based on disease risks, the effectiveness of the vaccines at certain ages, and how different vaccines may interact with each other. For example, the MMR vaccine is timed so that a child gets it just as they’re losing the residual immunity from their mother, generally around twelve months of age.

If you’re looking for the most advanced cold storage solutions on the market, you’ve found them. From concept to design, K2 Scientific’s vaccine refrigerators and freezers embody the true spirit of innovation. Contact us today.